Spiritual Space

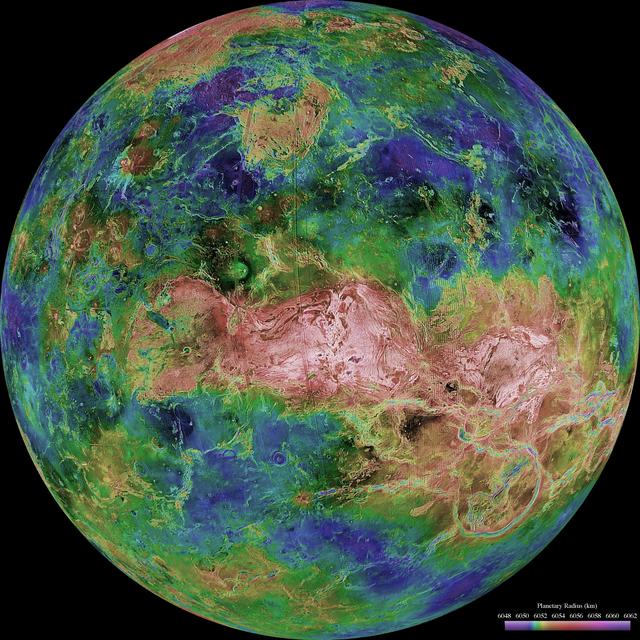

This is not how Lewis imagined Venus Credit: NASA/JPL/USGS

I came into my re-read of C. S. Lewis’s Space Trilogy (Out Of The Silent Planet, Perelandra, That Hideous Strength) with some trepidation. My world view has changed since I last read it 20 or more years ago. I remembered little of the first book, dreaded the second, and anticipated the third.

Lewis wrote the books, starting in the 1930s, after he and J. R. R. Tolkien agreed to write some science fiction stories. Lewis agreed to write one or more space stories; Tolkien was to write a time-travel story, which he never did.

Lewis already had a reputation as an academic and Christian apologist, but The Space Trilogy shouldn’t be mistaken for an adult version of his Narnia books. The two series have a few common characteristics, of course. Much of both stories take on worlds other than earth, the protagonists fall into their stories by accident or misadventure, and the stories are unapologetically Christian, though I think the Space Trilogy, being aimed at an adult audience, is a bit more subtle.

Science fiction writers usually demand a “gimme,” something beyond human knowledge or experience, for their stories to be believable. For much hard SF, it means we have to set aside the rules of physics so characters can travel faster than light and experience artificial gravity, or say that certain types of disasters have occurred or aliens have been discovered. Lewis’s gimme is the supernatural, a divine order to the universe. He’s not against science, but he believes there’s more to the universe than what science can know. The supernatural isn’t in opposition to the natural; it underpins everything. The supernatural is just more of nature, a part we can’t see, and therefore something many people refuse to believe.

In Out Of The Silent Planet an English philologist named Ransom (modeled after Tolkien) is kidnapped and borne away on a spaceship to Mars, known to its inhuman inhabitants as Thulcandra. It’s all pretty basic science fiction, until we learn both Malacandrans and Thulcandrans (those who inhabit the earth, The Silent Planet) are created beings. God exists and is an active force, evolution and the age of the cosmos are not up for debate, and the people of Earth, cut off from the rest of cosmos, understand only faint shadows of what is going on beyond the orbit of the moon.

Perelandra is the weakest of the trilogy because it’s not subtle. The reader needn’t be knowledgeable, much less sympathetic, to Judeo-Christian theology to read Out of the Silent Planet. But Perelandra expects us to know the Judeo-Christian creation myth, as Lewis re-imagines the Garden of Eden and tells a story of how things might go better the second time around: a new garden, a new Adam and Eve, a new snake, and a new advocate to argue against it.

It also celebrates the centrality of humanity in the creator’s design. Malacandra is a dying planet, a failed experiment. Its people, the sorns and hrossi and pfiffletrigi Ransom met in the first book, will eventually fade away, their planet ruined by conflict between beings larger than themselves. Those wars led to the fall of Thulcandra, but an experiment in redemption succeeded, making humanity’s story the pattern for the future of the universe. Lewis rewinds the tape, giving The Lady, Perelandra’s Eve, the burden of temptation but also providing Ransom to argue for rejecting it. All the decision-making rests on her, and it’s her obedience that pulls her whole world in the opposite direction of ours.

In our world, the blame for original sin, disobedience, rests on Eve. In Perelandra, (the planet we call Venus) the Lady doesn’t give in to temptation; there is no original sin, and Perelandra isn’t cut off from the rest of the universe like the earth was. I’m not familiar enough with Lewis’s non-fiction how he regards women in general, but many of his fictional protagonists are female. His girls and women have agency, make decisions, and suffer (or celebrate) consequences. If some of the misogyny in Western culture stems from how we’ve been conditioned to view the Eve of Genesis, perhaps this is Lewis elevating the spiritual view of women to be equal to that of men.

This is slightly closer to how Lewis imagined Venus, especially at the climax of “That Hideous Strength” Photo By Mattgirling - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16229901

That Hideous Strength is my favorite among the books. It has a sure place among the great works of dystopian fiction. It’s the most terrifying of the trilogy because its protagonists are ordinary people living in an everyday setting, and the aims of the antagonists — or more properly, their agents — seem so plausible in our post-Holocaust, post-Cold War, post-pandemic world. I have to remind myself it was written during World War II, when only the Germans knew what they were doing to the Jews and before modern science showed its horrible side. That it all comes down to demonic possession and divine intervention is disappointing (George Orwell thought so), but is consistent with Lewis’s worldview.

It’s also a conservative novel. Lewis is pretty clear in blaming Mark and Jane Studdocks’ marital problems on Modernity, especially society’s movement away from traditional Christian morality, not only their behavior but their views of each other and the world around them. To Lewis, a woman should still be subject to her husband, something that the events of Perelandra haven’t changed.

A deep dive into mid-20th century gender roles is beyond the scope of this essay (and probably the abilities of the writer). Lewis believed in a “universal morality” that all humans know and all humans not only violate, but are aware they violate. In this story he is arguing for a traditional view of relations between the sexes that he saw was already eroding, and would soon come tumbling down. Lewis himself kept mostly male company, and didn’t marry until late in life, but his views allowed him to prescribe a solution to the Studdocks’ marriage difficulties, the blame for which he spreads evenly: Jane is too independent, but Mark is too ambitious. By making them servants of one another, the Christian ideal, they begin to heal, as does their world.

We don’t need to agree with Lewis’s views to appreciate his skills as a writer and world-builder. Sixty years after his death, C.S. Lewis’ Space Trilogy is an important part of a legacy that still inspires writers and thinkers of all backgrounds. It was worth the re-read.